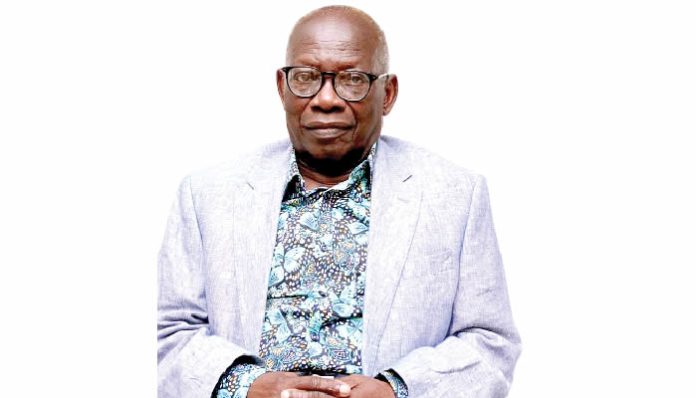

Professor Ilyas Adele Jinadu is a well-known professor of Political Science. He had been the President, Nigerian Political Science Association; Secretary General and President, African Association of Political Science and Vice President, International Political Science Association. He was also in the public service as a commissioner in the National Election Commission which became the Independent National Electoral Commission and Director General, Administrative Staff College of Nigeria, Badagry. In this interview, he speaks on the gale of defections of opposition figures to the ruling All Progressives Congress, the apparent apathy of the generality of Nigerians towards what these developments pose to the future of democracy, human development, and security in the country. Excerpts:

In a recent memo, you and some stakeholders raised the alarm that Nigeria was heading towards a one-party system. What are your concerns?

Our concern is that recent developments in our practice of democratic politics, going by the consequences of similar developments during our country’s First, Second, and current Fourth Republics, constitute a threat, and more seriously, a clear and present danger to the future of democracy and, therefore, development, peace, and human security.

These are already evident due to the lack of emphasis by governing parties since 1999 on pursuing public policies designed to prioritise the welfare of Nigerians, particularly the weakest and most vulnerable in our country.

The developments, as detailed in our statement, run counter to the struggle for democratic rule by various pro-democracy groups that ushered in the Fourth Republic in 1999. They are against the basic rule of democratic elections, which is that ruling parties must not misuse or abuse the power and resources of the state, including state institutions, for their parties’ partisan electoral advantage.

A Survivor’s Story: Trapped For 18 Following from this, our concern is also that the consequences of these developments will likely not create the fair and free electoral playing ground necessary to protect and ensure the popular electoral mandate they are expected to confer on winning parties.

In short, the developments reflect a common trend in our country’s electoral history, which led to the derailment of democratic politics during the First Republic in January 1966 and the Second Republic in December 1983, when competition rules were disregarded by generally unpopular ruling parties bent on winning the 1964/1965 and 1983 federal elections despite clear indications that they would not win in free and fair elections.

Finally, we are concerned about the apparent apathy of the generality of Nigerians towards what these developments pose to the future of democracy, human development, and security in the country. These developments are indeed nurtured and fed by this apathy among Nigerians.

What do you think is responsible for the ongoing gale of defections?

The sources of responsibility for the gale of defections are complex, but they involve the following interconnected dimensions of our electoral politics and our party and electoral system.

One, the abuse or misuse of the power of incumbency by ruling parties, especially at the federal level, for their parties’ partisan electoral advantage, used to blackmail, harass, or intimidate their political opponents in other parties.

Two, an amoral political culture that encourages impunity in public political life, especially as manifested in the approach to politics by politicians who see it as an avenue for corrupt personal enrichment, and the criminal deployment of the public procurement process by ruling parties at federal and state levels to accumulate a war chest and arsenal for winning elections.

Three, a weak party system that is not built on shared party principles or political ideology; one under which political parties lack internal democracy and reflect anti-democratic practices in their selection of party officials and nomination processes for electing party candidates for public office in the federal and state executive and legislature.

Four, an electoral legal framework that encourages defections through deliberate ambiguities in the electoral law regarding the conditions and consequences of defection and the recall of defectors who cross from the parties under which they were elected.

Five, the lack of a sense of public outrage against defections, which encourages defectors to feel emboldened because they are confident they can get away with it.

Do you think the defections are enough to guarantee victory for President Tinubu in 2027?

I do not know. We should wait and see how the configuration of events and omens in our political and socio-economic firmament unfolds to affect the 2027 general elections.

What should be the direction of the opposition/coalition in light of the ongoing defections?

Once defections start and the ruling party sets out to decapitate the opposition, the development can, in turn, set off a chain of reactions that may engulf not only the political class but also the country as a whole in a deluge of political crises that does nobody any good. It is for the rest of us, the citizens, to rescue the country from the politicians, and the politicians from themselves.

This is the lesson of our electoral history and the point made by Machiavelli and other political theorists in emphasising the republican virtue of placing the public interest above self-interest when the public interest is under attack by those who pursue politics as a self-interested vocation.

“Once defections start and the ruling party sets out to decapitate the opposition, the development can, in turn, set off a chain of reactions that may engulf not only the political class but also the country as a whole in a deluge of political crises that does nobody any good”

Do you think a coalition or opposition will be able to defeat the APC in 2027?

It is too early to say in the absence of a survey to determine this. As I said earlier, it all depends on future developments and events in the year before or in the terminal months leading up to the elections.

The North seems to be divided on Tinubu while the President is gaining more support in the South. Do you foresee a North vs South presidential election in 2027?

I do not believe in personalising politics. We need to look at the larger picture, especially the contradictions which the big men and women in politics are reacting to and trying to exploit or deepen in return. Ethnicity is a major driver, for good or ill, of our electoral politics.

What do you think our founding fathers tried to achieve through federalism?

What our founding fathers and mothers wanted to do by embracing federalism was to reconcile the push and pull of ethnicity as a building block of our federal system. But we have been unable to get rid of the mutual mistrust and fear of domination among the various ethnic leaderships of our political class that led to the adoption of federalism, defined as an ethnic federation.

What do you mean by ethnic federation?

An ethnic federation is one in which ethnic groups, no matter how defined, are granted some autonomy—self-rule in their ethnic homelands. In return, they are granted shared rule with other ethnic groups at the federal level. How to ensure shared rule at the federal level has remained the weakest link in our federalism, especially with respect to elections to the office of Prime Minister under our parliamentary system during the First Republic or to the office of the President under our constitutions since the 1979 Constitution.

Why is the issue of rotational presidency not taken seriously by politicians?

The federal character provisions of our constitutions since 1979 do not specify the rotational zoning of the Office of the President. When an attempt was made to insert a clause to that effect and to give constitutional sanction to six geopolitical zones during the constitutional conference convened by former Head of State Sani Abacha, it was rejected by the delegates to the conference.

If the problem of a rotational presidency along a North/South axis persists, it is due to the mutual ethnic mistrust and fear of ethnic domination that gave rise to the ethno regionalism of our 1951 Constitution and the ethno federalism of our constitutions since the 1954 Constitution.

The combination of mutual mistrust and fear of domination was also behind the crisis within the NPN during the primaries that led to MKO Abiola’s departure from the party. That was after it nominated President Shehu Shagari for a second term during the 1983 federal elections. This is contrary to the claim that Shagari would only do one term and step down for a southern NPN presidential candidate.

Controversy over zoning of the SDP’s party presidential candidate was a major reason for the annulment of the presidential primaries in August/September 1992, when some of the SDP presidential aspirants argued that they were opposed to the continuation of the primaries once it was certain that Gen. Shehu Musa Yar’Adua was likely to win the party’s presidential nomination.

In short, the zoning question has persisted because of the alleged breach of what some politicians see as a gentleman’s agreement on zonal rotation of the presidency within their parties, as was the case with the crisis over zoning that dogged the PDP during the 2023 general elections.

I have tried to put this problem in the context of the ethno regional foundations of our ethno federalism: mutual fear of domination by each other among the ethno regional majorities, and ethno regional minority fear of domination by ethno regional majorities. But it is a fear which ethnic factions of the leadership of our political class use to mobilise ethnic voting banks in support of their struggle among themselves for political power, through building coalitions across ethnic lines. This remains the puzzle to unravel and solve if we are to have national parties, other than shifting coalitions of parties that rely on ethnic voting banks to win federal elections.

The National Assembly has been criticised for being too submissive to the executive. What is your assessment of the Assembly?

In democratic theory, the legislature in parliamentary, but more so in presidential systems, is expected to subject the executive branch and the judiciary to oversight, just as the other two branches have some oversight role over the legislature. The hurry and speed with which the National Assembly has been performing its oversight role over the executive during its current session leaves room for great concern, even alarm.

For example, there has been little oversight over nominations for ministers and for other public political appointments requiring confirmation by the Senate, even when the public has voiced credible objections to some of the nominees. Budgets have been passed by the current Assembly without much debate or their details being carefully scrutinised.

The theory of separation of powers, mediated by the theory of checks and balances, is at the heart of democratic politics, and if the practice by the current National Assembly of not subjecting the executive branch to legislative oversight as the country’s Constitution stipulates continues, we are one step away from a single-party dominant authoritarian state, with the arrogance of power, impunity, and reckless abuse of power that it breeds, even in mature democracies.

This is why there is a need to strengthen the constitutional guardrails meant to act as sentinels in defence of democracy. Where this is not the case, where the guardrails are consistently trampled upon with arrogant impunity, the last guardrail remaining lies with the citizens, who must exhibit the republican virtue anchored on the demand for public interest policy. This is the message of the saying, “Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.”

Local government autonomy is yet to take effect eight months after the Supreme Court verdict. What do you think is wrong, and what should be done?

Local government autonomy will continue to be a problem so long as our political leaders cannot reach an elite consensus to extend the same limited autonomy or home rule that has been extended to state governments by granting local governments some limited autonomy from state governments. The theory of limited autonomy defining state–federal constitutional relations should, in other words, guide state local government relations. This is the general trend in many federations today.